Lesca got a strange phone call in the summer of 2021.

On the other end of the call, an immigration officer said, “We have your daughter.”

Yori, Lesca’s 9-year-old daughter, crossed the southern border by herself to get to Massachusetts to be with her mother. Lesca couldn’t believe that a girl that little had made the long trip from Guatemala.

Yori got off a plane at Boston Logan International Airport after a month in a shelter in Texas. She walked through a crowded luggage claim and into her mother’s arms. They had talked on the phone a lot after Lesca left her home country, but they hadn’t touched each other in almost seven years.

Lesca got another shocking phone call last month, almost four years after the federal government helped Yori get back with her mother.

Yori had been caught in Maine.

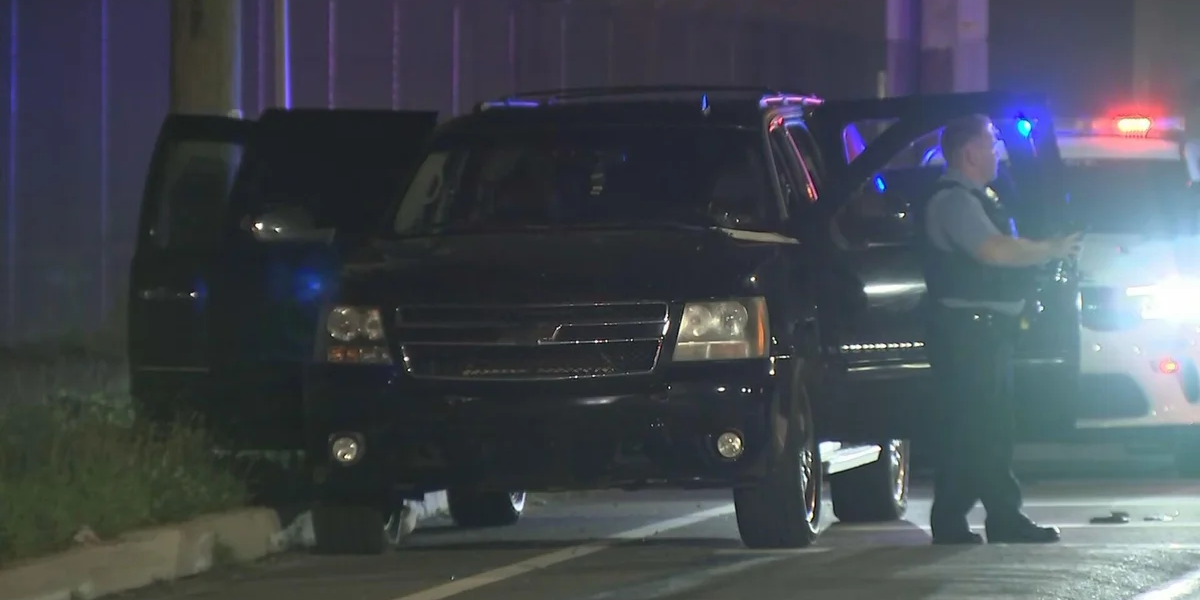

Yori, who is now 13 years old, was caught by federal immigration officers on May 23 during a car stop near Farmington. It took two weeks to get her back to her mother. The experience showed how the immigration detention system has changed and become more secretive during President Trump’s second term.

In a conversation with her mother, Yori said, “I was scared because they were taking us away and my mom didn’t know anything.” She was crying as she spoke. The Bangor Daily News decided to use nicknames for them because they didn’t want their real names to be used because it could hurt their immigration cases or the privacy of the minor.

The girl is an example of a child who got caught up in the president’s harsh raid on immigration. This includes children who the government had previously helped get back with a parent. It is harder to get kids back to their illegal families now that the president is a Republican.

Lawyers who worked on Yori’s case said it was surprisingly hard to get details about her detention, such as where she was, basic paperwork, and what would need to be done to free her. The case that started in Maine was taken over by the governor’s office in Massachusetts and a representative.

Arrests of illegal immigrants have reached all-time highs here and across the country. As part of the crackdown, children have been taken away from their families. In February, police stopped a 17-year-old driver on the Maine Turnpike in Falmouth and took him into custody. After getting back together with his mother as a child, the teen moved to Lewiston.

Trump and other government officials have said that they are going after dangerous criminals. A spokesman for U.S. Customs and Border Protection said in a statement that an officer stopped Yori’s car to check the driver’s immigration status and found that the man was a member of the MS-13 gang who was wanted for murder. Everyone in the car, including Yori and another woman, was taken because they did not have the right paperwork to be in the country.

The immigration lawyer for Yori, JoAnn Dodge, said she didn’t know that the driver, a family friend, had been accused of being a gang member by the federal government until the BDN asked the agency for comment. The BDN couldn’t get in touch with the man or his agent. No matter what the claim was, Dodge asked why the police didn’t just let her client go back to her mother after making sure that federal officials had already checked out Lesca as her guardian.

Lesca said of Trump, “He said after the election he was going after criminals.” Trump was speaking to her daughter at the time. The woman is not a thief. Criminals are rapists and killers, not people who are working and going to school.

Yori, a seventh-grader with long black hair, said she left her home in Framingham that Friday morning with a group of family friends for a camping trip in Carrabassett Valley over Memorial Day weekend. This was a repeat of a trip the group had taken the previous year. Lesca, who works in the restaurant and has two children born in the U.S., stayed behind to take care of Yori’s sick 5-month-old half-brother, she said.

A white truck pulled over the car Yori was in not far from where they were going, and a uniformed officer asked everyone about their legal status. “An alien currently in the U.S. illegally,” according to a CBP spokesperson, was the one whose out-of-state license plates led the agent to stop the car during a routine patrol in Livermore Falls.

To let other people in the hiking group, who were driving in different cars, know what was going on, Yori said the arrest happened on the shoulder of State Route 27 around New Portland. This is where she put a pin on Google Maps.

Two people in the group who followed the pin drop to her location caught her arrest on tape. A 21-year-old woman and a girl were being led by clothed officers into the back of a white CBP truck while their wrists were being bound in front of them. The BDN looked at stills from the video that showed this.

CBP said it does everything it can to get children back to their legal guardians, but the guardian often doesn’t have legal status and won’t let them. Lesca was afraid to pick up Yori herself, but she said she told an agent that she was Yori’s mother and would make plans to get her daughter the night of her arrest and the next morning.

Diego Low, who runs the Metrowest Worker Center, also known as Casa in the Framingham area, and helped Lesca while her daughter was in jail, offered to pick up the girl, he said in an interview.

She told him that Yori slept on a small mattress under an aluminum blanket at the border station in the Rangeley area for two nights. She cried into her mother’s phone at one point because she had misread a paper and thought she was going to be sent back to the Philippines, a place she had never been before. Even though Lesca was crying, she tried to comfort her daughter over the phone by telling her to pray.

Two days after Yori was arrested, on Sunday morning, two older women working for an escort service took the girl to the airport and put her on a plane, she said. She got to a place that she learned was a shelter for kids who are lost without an adult after a long car ride. The other girls, who had all just crossed the border and were waiting to be put with a sponsor, made her feel different right away. Yori’s mother was already a backer for her.

At this point in time, government policy was changing. The Trump administration recently changed the rules in a way that makes it impossible for undocumented parents to sponsor children. This is because they now need forms of identification and proof of income that are hard to get without legal status. The National Center for Youth Law took these rules to court in May on behalf of kids who had been detained for long periods of time. On June 9, they won a limited order.

Low said that the Massachusetts group of people working on Yori’s case had grown to include officials from the state’s Office for Refugees and Immigrants. They thought that the new federal rules meant Yori needed a new supporter who had legal permission to be in the country.

There was a problem with that plan that happens a lot in immigrant communities: Yori had a legal family member who was ready to sponsor her, but that person had to give the government information about their household, which included undocumented immigrants.

At this point, not even Yori knew for sure where the girl was being held. The only time her mother knew where she was was when Yori called every day. Low said that the caller ID showed Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. A picture of their text conversation shows that at one point, Lesca asked a shelter worker where her daughter was, and the worker told her that she wasn’t allowed to give that information.

Near the end of Yori’s second week in jail, things got more complicated when Dodge called the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the federal agency in charge of caring for unaccompanied minors. A representative told Dodge that they did not have any record of Yori in their system, according to the lawyer. Dodge was worried and confused, so she called Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to find out where her client was. ICE had the girl’s address listed for a shelter run by KidsPeace, a charity that helps kids.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement wouldn’t say anything because of a privacy policy that applies to cases concerning children. A voicemail left for a KidsPeace representative did not get a response, but someone who answered the phone at an address in Bethlehem confirmed that the group runs a shelter for kids who are alone. A spokesman for ICE refused to say anything.

Yori tried to stay cool the whole time, but she started to worry that she might not be able to go home for a while. A 17-year-old pregnant girl who was her best friend at the shelter had been there for four months. Her lawyers asked politicians in Massachusetts for help with her case. Thursday, June 5, the office of Massachusetts’s U.S. Rep. Katherine Clark, the No. 2 Democrat in the House, called the shelter to ask if an assistant could come by.

The next day, someone called Lesca and asked if she would pay for Yori’s flight home. No one close to her knew for sure what made the government decide what it did.

On June 7, Lesca walked into Logan’s luggage claim area a second time. The gate was the same one where she hugged her daughter many years ago. She was scared. The quick change of heart by the government made her think she was walking into a trap. Lawyers and other people helping the family stood nearby, ready to take notes if an immigration officer arrested the mother.

In the end, Yori came out of the home with a social worker. The woman’s face was completely hidden by a baseball cap, a black jacket, and, according to Yori, a mask that she bought and put on when they got off the plane.

“It took less than five minutes,” Low, who was there that morning, said. The woman left after taking a picture of Lesca’s ID.

“So she was given back?” Which way is the paper work? The paperwork wasn’t turned in, but she’s back in some way. Dodge said soon after finding out that her client was home. “I believe that everyone was surprised and happy.”

On Monday, Yori didn’t go to school. Her peers asked her if she had been sent away when she got back. She thought to herself, “They had no idea what she’d really been through.”

Yori was at home. For Lesca, the story wasn’t quite over yet. That woman, who is 21, was taken at the same time as Yori. Her friend is the mother of that woman. Lesca said that she was still being held somewhere in Texas as of the middle of June.

Lesca said, “My friend thought her daughter would be safe because she had an SSDI, a work permit, and an open immigration case.” “But we can see that doesn’t change anything.”

by

by